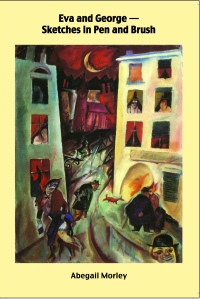

Eva and George – Sketches in Pen and Brush, Abegail Morley, Pindrop Press, £7.99

reviewed by Judith Taylor

When a poet draws on external material (history, biography, other artforms), the show/tell question is often tricky. Too much apparatus can diminish the poems and distract the reader, or indeed the writer (I speak as the author of a sequence which, but for wise editorial intervention, would have had not just endnotes but statistical tables): but an absolutist insistence that poems must stand by themselves also carries a risk, that those poems may have to contain (literally) too much information, too much that is properly the work of prose.

Abegail Morley’s pamphlet depicts the satirical artist Georg Grosz and his wife Eva Peter, in the period between their meeting in Berlin in 1916 and their emigration to the US in 1933. This takes in a lot of history, much of it grim. At the same time, readers are more than likely unfamiliar with Grosz’s art, which is central to the sequence. Morley largely avoids the pitfalls, giving the reader pointers, but not so many as to obstruct the poetry: a brief introduction and minimal notes to the poems; a small selection of reproductions to give a flavour of Grosz’s work; and a more detailed timeline kept to the end.

Her choice of Eva’s point of view is one I occasionally questioned: Georg’s own voice (as apparent in the two quotations that bookend the sequence) was articulate and engaging, and the second- and third-person of the poems sometimes imposes too much distance. On the whole, though, I think it is the right approach, letting us see the artist as well as the art, and making more explicit connections between them and the external events that shaped both.

It also allows the art to be described in something approaching lay terms: technicalities come in mainly in the vocabulary of colour, accessible to the reader and at the same time satisfyingly evocative and precise.

Ebert dies and you want to paint Germany cobalt blue,

say it’s the colour of silence, how it turns white

when there’s too much noise.

[‘Oil Painting: 1925’]

In poems that are mainly short, and plain in form, and which largely eschew imagery other than Georg’s own, the colours take us out of the literal into emotional and symbolic dimensions –

Sounds like boots. Black boots. Marching boots.

You tell me everything is schwarz, that your nightmares

throw their arms around you each night….

[‘1921: Deutschland Uber Alles’]

Even the ferocious ‘Burgerbraukeller: 1923’ dramatises the couple’s hatred, and fear, of Hitler almost in terms of art, albeit an art not Grosz’s own:

we want to slit him open,

drag the middle from himblack as bitumen,

lay him out like we’re morticians,inject his carotid artery, puncture

his hollow organs, fill his carcasswith Egyptian red gold

The cost of using Eva as our lens is the extent to which it effaces her – most startlingly when she describes the birth of their first child: “Peter Michael joins us in cadmium red” (‘1926: Stammhalter’) – although she was clearly a strong character in her own right. But where she is given metaphorical language of her own, as when she describes her husband

opening and closing your sketchbook

like it’s a pair of wings desperate to leave

[‘Widmung an Oskar Panizza’]

the effect is all the more striking. The clipped intensity of the early poems recreates very effectively the tense, constrained lives the couple lead in the early inter-war period.

At some points, however, the approach worked less well for me: the handling of external events is occasionally heavy-handed, most jarringly in the poem from 1921 just quoted, which ends

Hitler becomes leader

of the Nazi party – we wonder whose namewill last the test of time.

And in the later part of the sequence I felt events were being allowed to flash past too quickly, and an increasing reliance on our knowledge of the external context. The abrupt ending with the couple’s departure from Germany leaves a sense of unresolved struggle, particularly as the endnotes reveal that in a way they did not escape: poverty and depression followed them into their new life, and after Georg’s sudden death in 1958 Eva filed a successful restitution claim for the damage done to them by the Nazi persecutions.

I think, though, that the problem is not with the poems so much as with the constraints imposed by the pamphlet format. I would have liked to see these poems given more room to expand, both in historical breadth and in biographical depth. But as they stand they are a powerful achievement – an intense, unsettling and often salutary read.

Judith Taylor

http://www.deadgoodpoets.co.uk/judithtaylor/